In my last article, I spoke of the problems of believing it’s OK for companies to make money without any mind toward serving a social purpose.

Today, I want to turn to another problem: the idea of trying to serve a social purpose without making a profit, as so many non-profits do today.

In short, I want to ask: How can we expect to drive real change when we are constantly underfunded and in the pockets of corporate donors?

The Non-Profit Industrial Complex

I worked at a non-profit sustainability think tank for eight years. I interned for several non-profits before that. I loved working with people dedicated to making the world a better place. I loved feeling like I was having some sort of positive impact on the world. The thought of clocking in 9 to 5 for the sole purpose of making money – knowing I was very possibly screwing someone over in the process – felt soul-sucking.

At the same time, I often found myself frustrated. We never had enough money or resources to do truly transformative work. We never had the same access to decision makers as our corporate partners. We never seemed to have the same organizational rigor as the top-level companies.

Most importantly, over the years, I had a growing sense that I was contributing to a system and set of expectations that were hurting the world more than they were helping.

Here’s how that current system works a lot of the time.

Step 1

For-profit companies make a bunch of money, often by polluting the environment, making low-quality products, and by not paying their employees a living wage.

Step 2

Having made considerable amounts of money, eventually the owners set up a Foundation or philanthropic wing of the company.

Step 3

The Foundation gives a small percentage of the company’s profits to a bunch of non-profits, who go and do the “for-good” work.

Step 4

The non-profits are grateful to the company for the money and the company comes away feeling like they’ve done good. The public sees the company as generous and benevolent.

So What’s Wrong With This Picture?

There a few things wrong with this.

First, too often, the non-profits’ work is simply attempting to reverse the environmental and social damage caused by money-centric companies. We’d be much better off expecting companies to be environmentally and socially responsible in the first place.

Second, too often, the Foundations – as project funders – get to define project parameters, what’s “in bounds” and “out of bounds.” At worst, they can put a stop to anything that disrupts, undermines, or questions their company’s profit-maximizing practices. They can guide non-profits toward work that sounds and looks great, but keeps the status quo perfectly intact. Non-profits that really want to change the system usually don’t get funded.

Third, and maybe most problematically, this system creates and reinforces a core, highly questionable, and extremely unhelpful belief we have about our economy:

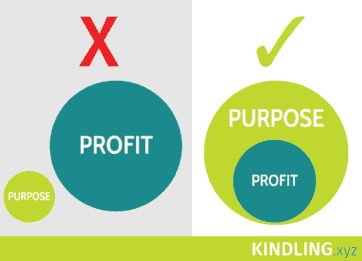

You can either make money or do good. You can’t do both.

A False Belief

Most of us have bought into this belief. You either go to a non-profit and do “good” or you go to a for-profit and make money. Right?

Is it possible this is simply a false dichotomy created by those in power? Consider this: Who most benefits from this set-up: those trying to make money or those trying to do good?

I’d say clearly those trying to make money are the ones who most benefit. Sure, there are some great tax breaks for being a non-profit, and that’s certainly how “non-profits” became a thing in the first place. But the flip-side of this agreement is the for-profits are let off the hook for serving any sort of social purpose. That’s for the non-profits.

The non-profits are the big losers in this system. Because they are non-profits, they often don’t build capacity to establish a sustainable revenue stream. So, they remain perpetually underfunded, have a hard time attracting and retaining top talent, and are often at the mercy of corporate donors.

The non-profits are the big losers in this system, yet they play a critical role in reinforcing and perpetuating it.

Many (including me for much of my life) wear the “non-profit” badge with honor. We are proud to do work that seeks to have a positive impact. We are proud to declare we put passion over profit. That’s a great thing.

But by labeling this work first and foremost “non-profit” (rather than “for-purpose”, “mission-driven”, “values-based”, etc.) we imply that profits are by definition antithetical to social good. We imply that the not making a profit part is the defining characteristic of these organizations. Through this language, we create a belief that profit is bad and not making a profit is good.

By shunning profit (even when it is in service to a greater purpose), we keep ourselves down – underfunded and in others’ control. By shunning profit, we leave the purpose-less organizations with all the money and power and yet no expectation to do good with it.

The New Paradigm

This leads me back to my original question: By “fighting the good fight” and working for a non-profit, do we not tacitly affirm and support the belief that “for-profits” have no responsibility to do good? By priding ourselves on our non-profit status, do we not keep ourselves under-resourced, disempowered, and marginalized? Is this not exactly what those benefiting from the status quo want?

What if we simply expected most organizations to both serve a social purpose and find a way to sustain themselves financially? With some clear exceptions, I think our society would work much better if a greater proportion of our organizations both created value for society (see my last article) AND were financially self-sufficient.

In doing so, we could dismantle the false narrative that one segment of our society does good and the rest of us are off the hook. We would move toward a society where all organizations are expected to provide some sort of net value to society. We would deconstruct this pervasive, destructive belief that separate purpose and profit as antithetical rather than equally essential.

You can either make money or do good. You can’t do both.

Wrong.

We can do both. We should do both. We must do both.